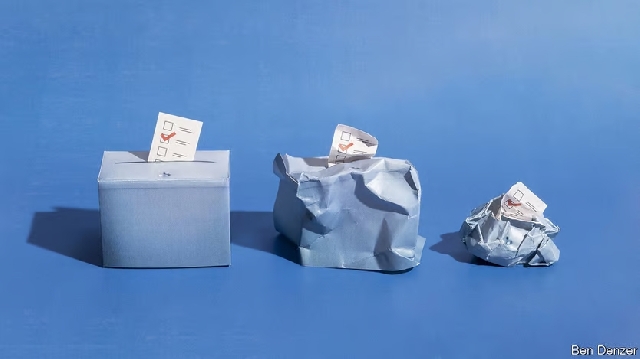

How to rig an election

Election materials

Election materials

Men rise to great fortune “more through fraud than through force”, argued Niccolo Machiavelli, a 16th-century adviser to unscrupulous princes. Modern potentates can find similar advice in “How to Rig an Election”, a book by Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas. “In many countries around the world the art of retaining power has become the art of electoral manipulation,” argue the two academics (who, to be clear, do not approve).

Only a handful of autocratic regimes, such as China and Eritrea, dispense with elections entirely. Most at least pretend to offer voters a choice, while making sure the opposition cannot win. It is a shrewd strategy. Regimes that practise what Mr Cheeseman and Mr Klaas call “counterfeit democracy” tend to last longer than pure dictatorships. Holding elections makes them seem more legitimate, so they are less likely to be ostracised internationally. And allowing an opposition gives them someone to demonise.

Several elections in 2024 will illustrate this sad truth. In some cases, the deception will be obvious. Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda, won 99% of the vote last time, so it is safe to say he will be re-elected in August. In Mali elections due in February were delayed for “technical reasons”. Voting is impossible in jihad-racked parts of the country and few expect the junta that seized power in 2021 to step aside.

Only a handful of autocratic regimes dispense with elections entirely

Most election-riggers are more subtle. They want to cheat just enough to win, but not so much that their country’s reputation takes a nose-dive. Rather than crudely stuffing ballot boxes on election day, they try to tilt the playing field beforehand, in various ways.

This starts with steps that are not directly tied to elections, such as handsomely paying the police and army to ensure their loyalty, co-opting judges, turning the public broadcaster into a propaganda megaphone and hounding watchdog groups into bankruptcy with meritless tax probes. Some leaders deploy convoluted legal arguments to evade term limits, as in El Salvador and Russia.

All this sets the scene for stage two: nobbling the election itself. By fiddling with electoral boundaries, rulers can make opposition votes count for less. By not updating the electoral roll, they can keep dead people registered—and the dead generally vote for the ruling party. Permits for opposition rallies will take months to process; ruling-party rallies proceed without a hitch. Some regimes quietly sponsor bogus opposition candidates to split the anti-incumbent vote. Expect plenty of this in Russia in 2024.

Real opposition parties are kept off balance with a thousand bureaucratic shoves. In Zimbabwe in 2023, strict but selectively enforced limits on campaign spending, combined with a sudden 20-fold increase in registration fees for candidates, left the opposition with little cash for campaigning, while the president swanned around in a helicopter. On election day itself, a mysterious shortage of ballot papers in opposition strongholds forced voters to queue until the small hours. No such delays afflicted ruling-party strongholds, where ferocious “volunteers” (who actually worked for the security services) sat outside polling booths checking ids and conducting an “exit poll” to make sure everyone voted for the president. All these tricks will be copied by others in 2024.

Popular opposition candidates are often barred from running for office—it is astonishing how many can’t seem to fill in their paperwork properly. Some are locked up; not for political reasons, of course, but for ordinary crimes such as fraud—one of the charges for which Alexey Navalny is serving 30 years in Russia. Rahul Gandhi, the main opposition leader in India, was sentenced to prison for defamation in 2023 and barred from political office; he managed to get the ruling suspended in time for the world’s biggest-ever election in 2024, but it wasted months that could have been spent campaigning.

If Bangladesh were to hold a fair election in 2024, the opposition led by Khaleda Zia would probably win. But Ms Zia is under house arrest after being convicted of corruption, and the ruling party is expected to triumph. The last time Belarus held a presidential election, the wife of a disbarred and jailed opposition leader almost certainly won by a wide margin, but the incumbent despot Alexander Lukashenko says she didn’t, and he has both guns and Vladimir Putin on his side. The next election, in February 2024, will be “fair, unlike elections in the United States”, Mr Lukashenko says.

Many people fret that technology—especially ai—will make election-rigging easier. The volume and verisimilitude of fake videos of opposition leaders doing unspeakable things will surely increase in 2024, and that may sway some voters, especially in countries with low literacy and declining press freedom, such as India and Pakistan. But ruling parties already had ample tools to spread disinformation, so the effect may be marginal.

Institutions matter more. In a country with ingrained democratic habits and robust checks and balances, it is hard for a leader to alter the result, as the United States discovered in 2020. For institutions to survive, however, voters need to care about them. If, in 2024, Americans re-elect the man who tried to overturn the 2020 election, they will have to live with the consequences.

Robert Guest, Deputy Editor, The Economist

Elections

The World Ahead 2024

This article appeared in the International section of the print edition of The World Ahead 2024 under the headline “Distorting democracy”

Published since September 1843 to take part in “a severe contest between intelligence, which presses forward, and an unworthy, timid ignorance obstructing our progress.”

Source: economist.com