Government of Ghana goes on a secret borrowing binge

Finance Minister Dr Mohammed Amin Adam

Finance Minister Dr Mohammed Amin Adam

Ghana has been hard up of late

Except for those who have been living under a rock, everyone knows that Ghana, once an African poster child of the Eurobond markets, hit a rocky patch in 2021-2022, defaulted on its international debt in late 2022, followed that up with a painful domestic debt restructuring, apparently the first in Africa, and has since mid-2023 been under an IMF program.

The country’s government, however, kept a good face in front of the world throughout the whole ordeal and has been touting a decisive recovery for much of 2024 to be crowned with upcoming successes in restructuring its international debt.

The whole recovery narrative and the credibility of its IMF sponsorship, nevertheless, rests on Ghana being able to present itself as a new paragon of fiscal discipline. Borrowing wisely and conservatively to spend carefully and thoughtfully is, obviously, the firm ground of such a posture.

The 2024 Borrowing Plan

Ghana’s 2024 national borrowing plan was thus of much interest to all observers, especially those in the investor community and in the civil society fiscal watchdog camp.

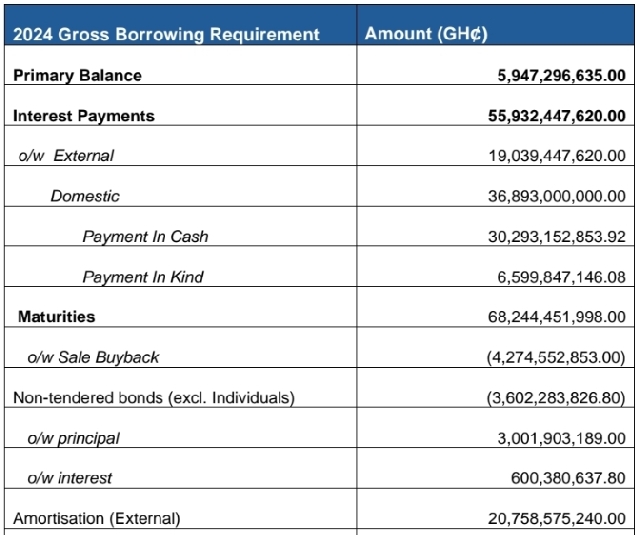

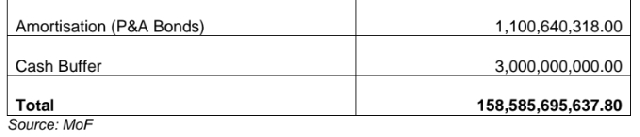

The country laid out a $10 billion borrowing roadmap to handle maturing obligations and to cover the gap between the government’s revenue and expenditure for 2024, as seen below.

Because a good chunk of borrowed funds always go to service and clear previous debt, the expected addition to the national debt from fresh borrowing in 2024 from local investors was just a little above $4 billion.

Because investors don’t trust the government too much, and it knows it, there wasn’t much hope of lenders giving it money for more than 1 year. The decision was thus made to rely almost exclusively on treasury bills, which are of 1 year duration or less.

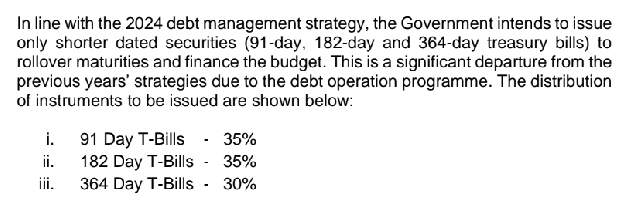

Three types of treasury bills – 91-day, 182-day, and 364-day – were to be deployed in roughly equal proportions to mobilise money for the government. The government swore, upon its good name, to ensure total transparency and predictability throughout the year in its routine visits to the market to borrow.

It became clear very quickly that the $10 billion borrowing target was not realistic. In the three successive quarterly issuance calendars that followed the release of the borrowing plan, gross issuance targets cumulatively crossed $13.5 billion, a worrying 35% sidetrack. And the fourth quarter hasn’t even arrived. Consider also that the government frequently accepted subscriptions above targets until investors began to cool on treasury bills in July.

Something dark lurking in the shadows

On the face of it, it would seem that all the country has to contend with is the usual target overruns. Dig deeper, however, and stranger shapes start popping up.

In the advance borrowing plan, and every quarterly issuance calendar thereafter, the government has stuck to a certain line.

* Only three types of treasury bill shall be used for the domestic borrowing program.

* To ensure total transparency and predictability, all market participants can rely on the issuance calendar, and the process will ensure a level playing field.

* Treasury bill issuances shall be done by primary auction, with the assumption, therefore, that they will be open to all the licensed primary dealers. Primary Dealers are companies allowed to buy government securities (like bonds and treasury bills) and then sell them onwards, wholesale, to the rest of the financial industry.

Extract from government of Ghana’s guidance for 2024 issuances

At no point has the government ever disclosed that it will be introducing new borrowing instruments into the market.

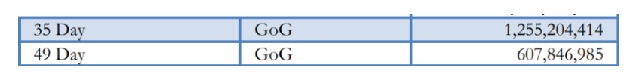

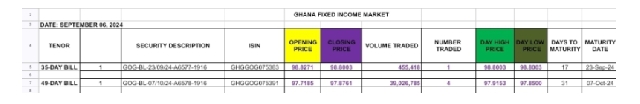

At any rate, the market rules require the public and market participants to be notified two weeks in advance before the introduction of new products. Yet, when three new instruments – 77-days, 49-days, and 35-days treasury bills – were introduced in haste in early 2023 because the conventional instruments were struggling due to the domestic debt restructuring (DDEP) and the aversion it created to lending long to the government among investors, this rule was simply brushed aside.

Most strangely, the government adamantly refused to mention them in its 2024 borrowing plan, and has fastidiously omitted mention of them in all its issuance calendars for the year. As of today, you won’t find any trace of them on the Bank of Ghana website, however hard you try.

The craziest thing, however, is that, in recent months, it has resurrected two of them – the 35-days and 49-days – and has been selling them in large volumes even though it only released roughly $200 million in the debut issuance.

It gets worse

As if the skulking itself isn’t an issue, there is also the refusal to use primary auctions to release these products into the market. Instead, a small group of primary dealers have been selected to hawk the bills door to door.

Over the past week, I have spoken to a number of market participants who have informed me that these short-term bills are being offered with far juicier interest rates between 29% and 35%. Even though on the secondary market, they are trading at close to par.

It appears that a tiny group of highly favoured dealers and brokers have been selected and given massive discounts on the bills without any requirement to underwrite a portion as they would normally be expected to do in their capacity as “market makers” in a competitive issuance scenario.

At the alleged interest rates, the cost to government of using these bills to plug the shortfalls it has been seeing recently at the open auctions of the more conventional types t-bill types (91-days, 182-days, and 364-days) is prohibitively high. From the data being reported to us by market participants, the implied monthly interest rate, depending on the precise discount level at the primary dealer level, could range from 15% to 24%. Bear in mind, also, that every week, the government tries to sell 1-year treasury bills to “normal investors” at an annual interest rate of just about 28%. A truly perverse “inverted yield curve” situation, that in conventional economies should suggest the risk of recession (adjusting for some financial and commodity price indicators).

The cross-cannibalisation effect of hawking lower-priced t-bills to parts of the market whilst trying to sell higher-priced t-bills in the main market to the rest should be obvious to all. If the scale of this side-trading escalates, or if it begins to affect expectations in a more fundamental way, there is no doubt that it will start to contribute strongly to the “undersubscriptions” being witnessed on the main market.

I put “undersubscription” in quotes because in Ghana, commentators misuse the reverse term, “oversubscription”. A true oversubscription would occur if once the government met its target it refuses to take more money. In Ghana, the government regularly accepts all the money offered above the stated target and still calls it an “oversubscription”. The usual justification for doing so is that “shortfall buffers” must be built. Closer to the truth is the acknowledgement that the loose targets speak to a fundamental challenge with strict fiscal deficit management.

Side-gigs galore

In the same intriguing fashion, it would seem, judging provisionally from the data being reported by Ghana’s market depositary, the CSD, that the government has been executing “tap issues” outside the primary auction system to a select group of favoured dealers even of the conventional 91-days, 182-days, and 364-days t-bills.

A tap issue means selling additional volume of a security like a t-bill outside and after the original auction at whatever price is agreed with the buyers. From my quick checks, 50% of all these tap issues for this year date from mid-August 2024. Pricing remains unclear.

There is thus a perverse sense in which the idea of “undersubscription” is contestable since the government appears to be selling large volumes of the same t-bills that it struggled to sell in its main auctions on the side, probably at a higher interest rate.

The escalating levels of these seeming tap issues suggest desperation. Recall also that, historically, Ghana only did tap issues for medium- and long-term notes and bonds, and only when market conditions suggested that it could get better rates. Doing tap issues at worse rates would be truly unprecedented.

Desperados in the heat

That the government appears to be facing a serious cash crunch is amply borne out by the sum effect of borrowing even more deeply on the short-end. It appears that since even 91 days is proving too long for some prudent investors to leave money with the government, it is being forced to borrow at 35-day intervals. But by doing so, it seems to have heightened its attraction to yield-hungry speculators with no reason to care about rollover risk.

There is a reason why very few countries use super short-dated treasury bills for mainline government borrowing. The likes of Tanzania may have resurrected 35-day bills in 2002 for cash management purposes after discontinuing them, and the Philippines may have done so in 2020 to serve as a liquidity lubricant during the pandemic, but it is not often that a government is forced to introduce them to help game market sentiment. Both Tanzania and the Philippines used open market auctions to sell these and all their other treasury bills.

The government of Ghana’s strategy of using low-publicity tap-issues and undercover super-short term t-bills to borrow money at shylock rates whilst trying hard, at the same time, to create the impression that its borrowing costs are dropping on the main market is clearly too clever by half. It doesn’t take too much for market participants to decipher these, frankly, woozy moves.

Sadly, all of these fiscal side-gigs have a real effect on accelerating the debt build up since high borrowing rates mean higher levels of maturing obligations over time.

Unless there is something we have missed entirely in our reading of the picture, the whole IMF-backed fiscal consolidation program is beginning to look like one big voodoo display.

Source: brightsimons.com

Trending Features

Ghana: 68 Years of nationhood sailing through the turbulent times

13:29

Ghana Gold Board(GoldBod) is a very serious error in Judgement

07:28

Review of the 1992 Constitution, too late or too early?

14:40

Kwesi Pratt NOT fit to unloose the shoes of Dr. J. B. Danquah

03:42

Full text of Mahama's maiden budget

10:55